14th May 2014. Multinational corporations are infamous for pushing native people off their land in order to open a new gold mine, extract oil, or otherwise extract local resources. For decades, backlash has been thought to be both limited and ineffectual, but new evidence suggests that protests from local people are effective, extremely costly for the companies, and often lead to substantive changes to or total abandonment of a project.

14th May 2014. Multinational corporations are infamous for pushing native people off their land in order to open a new gold mine, extract oil, or otherwise extract local resources. For decades, backlash has been thought to be both limited and ineffectual, but new evidence suggests that protests from local people are effective, extremely costly for the companies, and often lead to substantive changes to or total abandonment of a project.

Researchers at the Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining interviewed employees at several dozen major international corporations who are involved with extractive activities, and found that companies are increasingly having to deal with the social and environmental impacts of their work, and that it’s hurting them where it hurts most: their bottom lines.

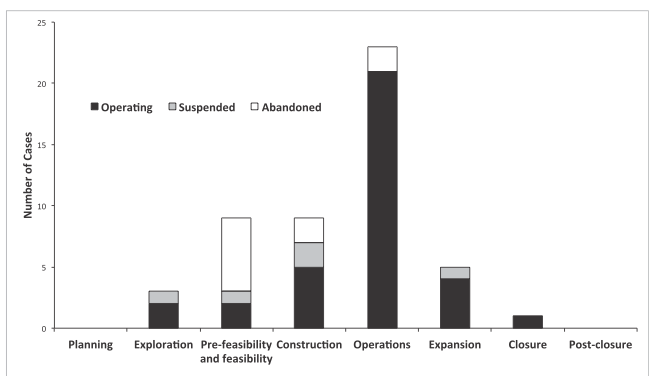

The researchers, led by Daniel Franks, took a look at 50 planned major extractive projects (oil drilling, new mine construction, that sort of thing) and found that in fully half of them, local people launched some sort of “project blockade.” In 40 percent of the projects, someone died as a result of a physical protest, and 15 of the projects were suspended or abandoned altogether, according to Franks’ study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“There is a popular misconception that local communities are powerless in the face of large corporations and governments,” Franks said in a statement. “Our findings show that community mobilization can be very effective at raising the costs to companies.”

The reason these projects, such as the Minas Conga gold mine in northern Peruand Lanjigarh bauxite mining project in Orissa, India, were abandoned wasn’t borne out of some sense of social responsibility to not pollute the environment or to not push people off their land. It was because the protests and resulting government backlash was so great that it became financially unviable to move forward.

Delays, even early in a project, can be extremely costly—at a major mining project, $20 million per week in lost revenues and lost investment isn’t uncommon. According to the study’s respondents, a nine-month delay at a Latin American mine cost a company $750 million; protests that shut down power lines at another operation cost $750,000 a day. Even before drilling or extraction has started, lost wages and startup delays can cost $50,000 a day when programs are forced to a standstill after they’ve started.

Perhaps not surprisingly, protests were most successful when they took place early on, during feasibility and construction phases of a project.

“This [is] in part because the project is smaller in scale and therefore easier to contest, but also because at later stages of the project cycle, capital has been sunk into an area, changes become costly to retrofit, revenues begin to be generated, and there are increased incentives for companies and governments to ‘defend’ their projects,” Franks wrote.

Social media and internet access are allowing indigenous and local groups to organize more quickly, to learn from others who have had successful protests, and to connect with nonprofits and humanitarian groups that can help push their stories out to the entire world.

“There’s been a big change in the mentality of indigenous people—things like Facebook are allowing them to not be as naive,” Kelly Swing, a Boston University researcher who works in an area of the Ecuadorian Amazon that is currently fighting back against proposed oil projects, told me. “They look at what has happened in, say, Peru, and see that their culture has gone to hell in a handbasket. All of a sudden, gifts the companies offer, like boats and education and modern medicine aren’t the panacea they used to seem.”

Companies, for their part, are learning how to anticipate these sorts of hangups, and some of those interviewed (all identities and specific responses were kept confidential) said that local backlash can be predicted and quantified before it happens.

“Several interviewees were strongly of the view that the triggers for and underlying causes of company-community conflict, and its costs, are predictable, and that approaches, procedures, and standards are available to companies to avoid conflict and develop constructive relationships with community actors,” Franks wrote.

At many companies, Franks wrote, the higher ups who approve major projects are completely oblivious that their work might have some sort of social or environmental impact. To combat this, companies hire “translators” who are able to identify potential social problems and put them in a language executives can understand: money.

“Translation requires individuals within organizations who can work across functional, organizational, and conceptual boundaries, and who can work in more than one ‘language’ and interpret how social and environmental risk is translating into costs for business. The need for internal ‘translators’ suggests that corporate decision-makers do not currently have the necessary models to internalize externalities and translate social risk inward,” Franks wrote.

Franks wrote that there’s some evidence that companies really do want to make sure local people are treated correctly—that, as he found, concerns such as drinking water contamination, environmental destruction, and public health risks, are not brushed aside. Then again, he noted that “some see stakeholder-related concerns as optional ‘add-ons’ to broader regulatory processes for operating projects.”

The challenge for those “stakeholders,” then, is making sure that, no matter what, they make a project so difficult to complete that those “add-ons” become so costly that the project dies. It seems like, in an increasing number of cases, that’s actually happening.

14th May 2014.

14th May 2014.