The Intensification of Independence in Wallmapu

The Intensification of Independence in Wallmapu

Critical Reflections on a Solidarity Trip to Generate Electricity in one Mapuche Community in Struggle

John Severino

Introduction

In the last decade, an increasing number of Mapuche communities have carried out the “productive recovery” of their lands. Using direct action to take back their traditional territory from whomever has usurped it—usually logging companies or latifundistas—they take this land out of the capitalist market and put it to a traditional use for local needs, either through farming, grazing, or forest commoning. While this line of struggle has been hugely successful, inspiring other communities to begin forcefully taking back their own lands, those that have ejected the usurpers and asserted their claims to the land have often faced new problems.

After a community successfully reclaims its lands, repression usually decreases and quality of living improves, leading to a different atmosphere in which the struggle is less conflictive. In this new, more comfortable atmosphere of struggle, certain recuperative ideas can sneak in. One of these is the temptation to put newly acquired lands to economically productive use, out of a desire to achieve a higher standard of living along Western lines.

Closely related to the infiltration of a capitalist worldview, principally seen in the desirability of jobs and money, is the influx of evangelical Christianity. Evangelical churches are recruiting aggressively in South America, and their presence is always accompanied by a decrease is solidarity, an extension of the capitalist worldview, and a greater vulnerability to resource extraction and other development projects. Specifically in Wallmapu, evangelicals often work as snitches and they aggressively demonize the Mapuche culture. Communities in which the Christians have not yet taken root have a clear and effective solution—burn down the churches—but communities with an already significant Christian presence have lost their togetherness after the more conflictive moments of struggle passed and Christians could begin pushing for a successful reintegration into winka society or simply ignoring the earthly reality of social conflict.

Another major problem stems from the lack of access to electricity and water. Most Mapuche communities steal their electricity from existing power lines. But in the depths of the forestry plantations that occupy the greater part of Mapuche lands, there are no power lines to pilfer from. What’s more, the exotic, genetically modified pine and eucalyptus planted in straight rows in a nearly endless monoculture (the World Bank labels these as “forests” in its development statistics) dry up the water table. In other words, many Mapuche communities have successfully kicked out the logging companies or big landlords, only to find that they could not have electricity and water in their newly reclaimed lands. Taking advantage of the vulnerable situation, logging companies and NGOs used charity to discourage resistance, building infrastructure projects to reward non-conflictive communities.

To overcome this obstacle, some Mapuche communities in struggle have begun looking for ways to set up their own water and electricity infrastructure. In the furtherance of this goal, one community invited a handful of gringo anarchists with the necessary skills and resources to help them set up an electricity generation system that could subsequently be recreated in other communities. This article is about that collaborative project.

The Community

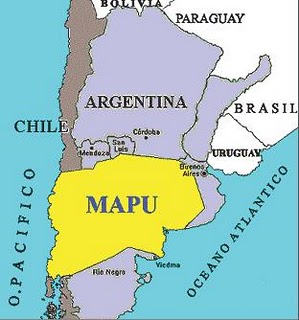

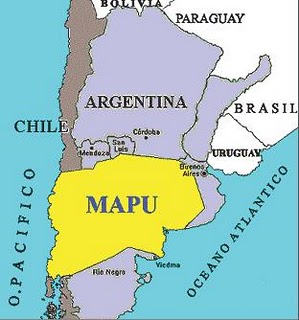

We can call the community where the project took place Lof Pañgihue. The people of Lof Pañgihue lost their lands, along with the rest of the Mapuche, in the 1880s during the surprise invasion by Chile and Argentina. As with other lof, many che were killed, and others became refugees, eventually moving to the cities. A few were able to remain in the lof and rebuild, though their herds and the best of their lands had been stolen from them. The rewe, ayllu rewe, and fütal mapu with which the Mapuche had traditionally come together for ceremonies or defensive warfare had disintegrated.

The Chilean government was giving away Mapuche lands, and many gringos came and set up large estates on which the Mapuche had to labor as peons. The struggle in the early years was focused on survival, retaining their language and spirituality, and resisting the landlords. In the days of Allende and Pinochet, the Mapuche linked their struggle with the leftist anticapitalist movement in force at the time, often joining armed struggle groups like MIR and Mapu-Lautaro. Around that time, several thousand people were living in Lof Pañgihue on just about a hundred acres of land. A large amount of land was nationalized by the Allende government as part of a program to eventually give it to poor people (Mapuche and winka) on an individualized commodity basis. The Pinochet government, however, gave this land to the logging companies, and Lof Pañgihue was soon surrounded by pine plantations.

In the early ’90s, many Mapuche embarked on an autonomous line of struggle, increasingly rejecting the leftist mode of struggle that had utilized the Mapuche as footsoldiers, or the Marxist analysis that insisted on branding them as peasants who had to join the international proletariat in order advance and liberate themselves.

In the early ’90s, many Mapuche embarked on an autonomous line of struggle, increasingly rejecting the leftist mode of struggle that had utilized the Mapuche as footsoldiers, or the Marxist analysis that insisted on branding them as peasants who had to join the international proletariat in order advance and liberate themselves.

The people of Lof Pañgihue occupied about a thousand acres that had been usurped by various latifundistas, using sabotage, attacks on police guardians, and constant pressure to eventually get the landlords to give up their claims. They also built houses and began farming or grazing on the recovered land. More recently, they began recovering another thousand acres currently usurped by a logging company. They have been cutting down pine for use as firewood and replanting native trees. With the return of the native trees, mountain lions, native birds, and other forms of life have also started to come back, including medicinal plants that the machis gather for traditional cures.

Multiple members of Lof Pañgihue have been imprisoned, and others face an array of minor and serious charges, in retaliation for their struggle. The police maintain a constant level of repression against the community, and they have also destroyed houses, stolen tools, tear gassed babies, shot rubber bullets at the elderly, and beaten, harassed, and arrested their weichafe, werken, and longko.

In the face of the repression, a neighboring community gave up on land recovery actions, even though many in the community still did not have any land. In another controversial decision, they also accepted a charity project from the logging company that brought water to the village. But after just a couple years, the pipes broke, and the community has neither the know-how to fix them, nor the money to pay for replacement parts. That enforced dependence is a built-in part of charity. The logging company rewarded the community for giving up its struggle, but it was not so stupid as to hand out a reward that would permit any degree of independence. They did not involve the community in building the infrastructure, nor did they use cheap local parts that could be easily replaced.

In the face of the repression, a neighboring community gave up on land recovery actions, even though many in the community still did not have any land. In another controversial decision, they also accepted a charity project from the logging company that brought water to the village. But after just a couple years, the pipes broke, and the community has neither the know-how to fix them, nor the money to pay for replacement parts. That enforced dependence is a built-in part of charity. The logging company rewarded the community for giving up its struggle, but it was not so stupid as to hand out a reward that would permit any degree of independence. They did not involve the community in building the infrastructure, nor did they use cheap local parts that could be easily replaced.

The major obstacle faced by Lof Pañgihue is the lack of water. Thanks to all the pine plantations, the middle of the valley where they and the other community are located goes bone dry in the summer. No water for drinking, no water for the animals, no water for the crops. There are year-round streams at the edge of the valley, but no power lines to steal electricity from. They don’t need a lot of electricity, since they are not pursuing a Western model of development, but having radio and telephone is not only a major convenience, but a way that different communities stay in contact and spread the word about repression. And, let’s not romanticize, the occasional washing machine is seen as a big plus.

If they can relocate their homes and gardens to the riparian side of the valley, leaving their current site for grazing, and if they find a way to generate power, then they will have land, electricity, water, their dignity, and a way forward in the struggle, whereas the community that accepted charity and made peace with the State will only have electricity and half the land they need.

The Anarchists

We got the invitation through a Mapuche friend we had worked with on our previous trip to Wallmapu. Having been their guest, and having collaborated on land recovery, translation and diffusion about their struggle, prisoner support, and other projects, we had a personal basis of trust, solidarity, and friendship. Without that, they never would have thought of contacting us when they learned that a nearby community needed to find a way to generate its own electricity.

The next step was finding comrades who were interested in the project and had the needed skills. We prepared for several months making arrangements, getting resources together, and practicing techniques for the fabrication of different generation systems.

We also talked about our expectations and desires for the trip.

A clear priority for everyone involved was a total rejection of charity. We did not see ourselves as privileged people going to help underprivileged others, nor as allies to the Mapuche struggle. The only reason we considered going was because the Mapuche were struggling for their freedom, and we as anarchists were involved in a distinct but interconnected struggle for our own freedom. This was, in a sense, the “community of freedoms” Fredy Perlman writes about.

The purpose of the project was to deepen the relationship of solidarity between different people in struggle. We were being invited because of specific skills some of us had, but we had no illusions about being unique in that regard. Only because the Mapuche had created such a potent, insightful struggle was this project even possible. It is no coincidence that none of us had ever set up an electricity generation system before; never before had doing so held revolutionary implications. We wanted learning on this trip to go both ways, and we knew that it would. Speaking for myself, the conversations and experiences I had on the previous trip to Wallmapu, the worldview and the vision of struggle I encountered, forever altered my own practice as an anarchist.

Because it was impossible to communicate directly with the people in the community until we arrived, when planning the trip we decided we should begin with a conversation about our goals, motivations, and expectations. We would not get distracted by the technical details, as important as they were. We were not going to set up a generation system in a village, we were going to deepen our relationships. The material infrastructure was an anchor that would permit the intensification of anticapitalist relations, and a point of leverage for the liberated social relations to push back against the imposed capitalist social relations.

As such, success for the project could be defined as the following:

1: forming relationships that would enable mutual solidarity

2: working together with peñi and lamuen in a collective process to install one or several models of electricity generation using local materials, with an emphasis on passing on skills, such that the model could be recreated without external aid and set up in other communities in struggle.

In other words, if we effectively set up an electricity generation system in a community and left, and the people there did not know how to make another one on their own, the project would have been a failure for us.

The Project

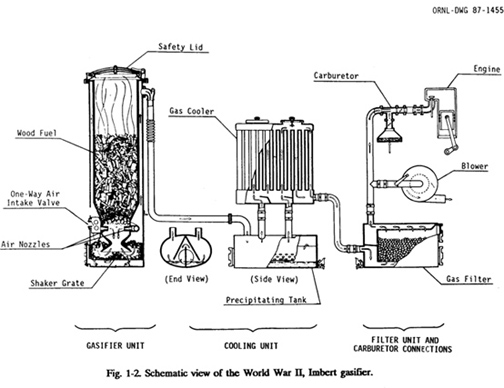

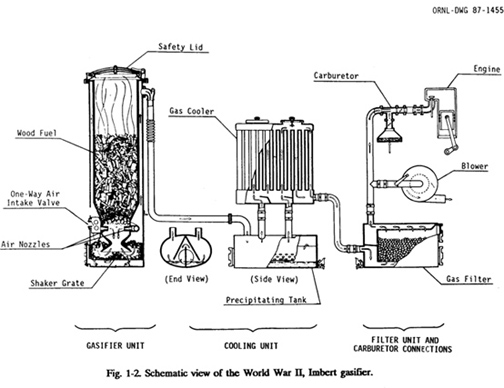

Solely on a technical level, the project was fairly complicated. The plan was to fabricate one system that would use wood chips to create power, and one or two run-of-river systems that would use pressurized water to turn a drive shaft and generate electricity.

Logistically, it became even more complicated. We needed to get a workshop space, an arc welder, a gas welder, an angle grinder, a drill, a metal lathe, a dozen hand tools, and a hundred other items that would constitute the primary materials. We had to get the materials as cheap as possible, in local stores and junkyards, so we could be sure that the peñi and lamuen could replicate everything after we had left. Then we had to build everything with Mapuche comrades so that they would learn the process. And we had to do all this in a context of constant repression, with new arrests and raids happening every week, some of them directly impacting on the project. The possibility of being arrested, deported, and banned from Chile hung over us throughout the entire project, should the state decide to define what we were doing as a political activity. The Chilean constitution prohibits foreigners from participating in political activities, and the state’s repression against the Mapuche specifically aims to isolate—one community from another, and all of Wallmapu from the outside world. To us, the project was not at all a “political activity,” in fact it went far deeper, and precisely for that reason we had to be extremely careful and low key.

A couple of friends took us out to Lof Pañgihue for the first time. The police seemed to know we were coming and controlled us near the entrance to the community, but that was hardly unexpected, given the level of surveillance they use against the Mapuche struggle.

The initial conversation between us and the longko and several werken and lamuen of the community went as well as we could have hoped. They explained their struggle to us, and the history of their community: the loss of their land with the Chilean invasion, further losses during the Pinochet dictatorship, the manipulations of their Marxist allies, the autonomous path of their struggle, the beginning of forceful land recoveries, the repression, the lack of water, the dependence on state electricity infrastructure.

Then we explained why we were there, that we were anarchists fighting against the State, that we respected the Mapuche struggle and wanted to create stronger connections of solidarity, that we came to help them set up a system for generating electricity but it was absolutely important for us not to create dynamics of charity. We recognized that we would be gaining a great deal from them, and learning things that would be helpful for our own struggle.

They thanked us for coming and asked us what models we were proposing to build. The only models for ecological electricity generation that they had had contact with were wind and solar, which in their region were only ever used by rich landlords.

We explained the two systems and their benefits. They were much better suited to the region, geographically and climatically, then wind or solar. They were more discreet, harder for the police to find and destroy during a raid, and cheaper to replace should they be broken. They would not hurt the land: the wood system only released as much carbon as the trees serving as fuel had taken out of the atmosphere, meaning as long as they weren’t deforesting their land there would be no net pollution. The only other waste product was charcoal which could serve as fertilizer. And the water system only required a small stream running down a slope. The stream would not have to be extensively dammed or diverted, and all the water taken from it would be returned to it. Both systems could be made with materials available in the stores and scrapyards of the nearest city.

We told them we had raised the money for all the costs of installing an electricity generation system, but to expand that system to meet the needs of the whole community, or to set one up in another community, they would have to meet those costs. However both models were designed to be highly economical and durable. The most expensive, inaccessible part was the alternator in the water system and the generator in the wood system, but the cost was not too great for a whole community to assume.

They liked the proposal, and they took us out to the site to make sure the geography and the available water supply were adequate. Then we had lunch together and talked a while about our respective struggles. In the evening we made ready to head back to the city, where other Mapuche comrades were looking for tools and a workshop. The werken from Lof Pañgihue said they would hold an assembly for the whole community to decide on our proposal, but he was sure everyone would be excited about it, as they had been talking about the need for such a project for some time. They would call us soon with confirmation and measurements from the site so we could start getting materials, and then they would arrange to send some people to the city to work alongside us and learn how to build these systems.

The day could hardly have been more fortuitous, but we encountered an early problem that would later create serious difficulties. Although we had been preparing on our end for months, because of limited and insecure communication, preparations in Wallmapu had not been able to move forward. The community had been able to send out its request, but had not been able to get detailed information about the specific proposal in order to start preparing. The logistics on this project were far more complicated than on the project three years ago, requiring local knowledge and very specific skills, and we did not have the direct connections to begin organizing those logistics until we arrived in Wallmapu. But as they say, sometimes you need to do something before you can get the skills and resources you need to be able to do it. This was definitely the case with our project.

But initially, back in the city, things went fast. Other Mapuche comrades who were friends of the friends we made last time helped us find the cheapest shops and the best junkyards. It helped immensely that several of them were welders, mechanics, or other technical workers, so they had all the necessary tools and knew where to get things we never could have found in a month.

Shortly, we got confirmation from the community that they wanted to work with us to realize this project, but they had to delay a bit before they could come to the city. So we waited. Days turned to a week before they told us they would not be able to come. Repression clearly played a role in this, but it also made us worry that the project would not be fully participatory, that it might slip across the line from solidarity to charity.

We had not wasted the entire week, since we continued getting to know the comrades in the city, sharing meals with them, learning the local histories of struggle, sharing stories about our own battles. But there was no way around the fact that our time there was limited, and with one week less, we were beginning to lose the chance at the nice leisurely pace we had originally envisioned.

We had not wasted the entire week, since we continued getting to know the comrades in the city, sharing meals with them, learning the local histories of struggle, sharing stories about our own battles. But there was no way around the fact that our time there was limited, and with one week less, we were beginning to lose the chance at the nice leisurely pace we had originally envisioned.

Discussing it with everyone involved, we decided to start fabricating the systems with a couple peñi from the city who were already experienced welders or builders. They would then be able to show others how to make the systems.

Still, we had vastly different rhythms. The peñi worked full time, and sometimes on weekends too, and they also had a completely different concept of punctuality. It soon became clear that to get done in time, we would have to do a lot of the fabrication ourselves, and then on our relatively short time together focus on practicing vital techniques and explaining the overall process of fabrication.

It was far from ideal and all the delays and time alone made us entertain serious doubts. Were we giving more importance to this project than our Mapuche comrades? Was the shared participation we were striving for a lie? So we (this being the reduced group of gringo anarchists) talked it out and decided that if the promised participation was not forthcoming, we would leave the two generation systems half-finished and head for home. It was neither an ultimatum nor a surrender, just the recognition that letting solidarity devolve into charity would be the worst possible outcome of the trip. It was far better, from the perspective of anti-State struggle, to leave half-completed systems rather than fully completed systems, because that meant that the generation systems would only ever be more than semi-expensive junk if the people they were intended for learned how to finish making and installing them.

Fortunately, we were able to have a heart-to-heart with a couple of the peñi in the city, both of whom helped set us straight. Having a heart-to-heart conversation about the possible failure of a major project is no easy matter, especially when there are huge cultural differences and the other people involved, while friends of friends, were total strangers until a few weeks earlier. The outcome underscores the importance of good communication and solid relationships based on friendship. The “dead time” we had spent waiting for the chance to get to work, and instead hanging out with new friends and getting to know one another, was more important in the end than the technical work on the systems, as the latter would have failed without the former, and the former—the good relationships—opens a whole world of possibilities and other projects.

The comrades we spoke with clarified for us how little detailed information had gotten through before our arrival, making it impossible to prepare in advance. They told us how enthusiastic many of them were about this project, and how such a project constituted an important and needed step forward in their struggle. They reiterated how they had limited time, and while they were fully committed, could not help out more than a few days a week, which just didn’t mesh with our schedule of coming for a month and working every day. And they clued us in that Mapuche from the countryside operated on a completely different calendar and there was absolutely no way around that. While those who lived in the city might say 8 and arrive at 10, the Mapuche from the countryside would say Monday and arrive on Wednesday.

Being told that it was a question of different rhythms helped us understand the difficulties we had been having and feel good about the time that had gone by, since we had no desire to impose our pace. The local rhythm will always take precedence over whatever expectations of rhythm outsiders may bring with them. In short order we saw ample proof that the Mapuche comrades in no way lacked commitment, and it was in fact still their initiative.

But the fact that we so closely approached defeat, in my mind, was perfect. It forced us to draw a line, to define victory, and we decided it was better to accept failure than to declare a false victory.

Shortly thereafter, a couple peñi from the community arrived, helped us get a few more materials that had so far eluded us, and took us and the equipment back to the lof. We worked feverishly the next few days, as we had pushed back our timeline considerably and our return dates were approaching. But the work in Lof Pañgihue was incredibly inspiring. We woke up every morning while the stars were still out, the lamuen set up a cooking fire, we discussed the day’s work together, and some of us cooked or acquired materials while the rest of us labored together along the river bed, speaking in a mixture of Spanish, English, and Mapudungun, digging, building frames, reworking the turbine, and installing the electronics. When it got dark, we would stop, but the conversations about the project and about our larger struggles would go on over supper and until midnight.

At the end of it all, seeing the pulleys connected to the alternators begin to turn, that unassuming circular motion was one of the most beautiful sights.

Affinity and Difference

When working together with anarchists from another country, you typically find that you speak the same revolutionary idiom and share an overwhelming affinity which is put into sharp relief by certain cultural and historical differences, which often prove useful for self-reflection by the contrast they provide.

Working together with Mapuche who are struggling for full independence, the gulf is even wider. Our histories share few common reference points (though these are of extreme importance), our worldviews are different, and we communicate within distinct idioms of struggle. The strong points of affinity capable of bridging this difference have all the more meaning, and reflect on anarchist ideas about decentralized global struggle.

Neither the Mapuche nor their struggle are homogenous; however in general they have chosen to frame both of these as unified entities. Some Mapuche believe in political parties, in NGOs, or in Marxist dogma about economics. But one aspect of their shared framing of the struggle is a focus on the communities and the land. This is the center of the Mapuche struggle, where communities are regaining their land, and it is precisely where leftists, NGOs, and political parties have the least hold. The former are all given a niche by the institutions of the State, whether the media, the universities, or the development funds, meaning they tend to only have a presence in the cities.

Among the Mapuche in the communities, or those in the nearest cities who focus on aiding the rural struggle rather than leading it, there is a clear tendency to reject the State, capitalism, Christianity, and the entire Western worldview, including the pernicious narrative of progress.

Many peñi and lamuen we met had a crystal clear view of what was going on in Bolivia and how much it represented what they wanted to avoid. The “plurinational state” of the indigenous Evo Morales had recognized various indigenous peoples within Bolivian territory, putting their rights down on paper, and this had changed absolutely nothing. Legal recognition meant nothing as long as they did not have their land. But “having their land” in the Western sense was also meaningless, because it would only imply individualized title to a commodity that had to be put to productive use on the market in order to be maintained.

The Mapuche are the “people of the land.” In their idiom, as with many other indigenous peoples, “having land” is interchangeable with “belonging to land.” It cannot be just any land, divided into parcels. It must be the land with which they have a historical, spiritual, and economic connection. Mapuche land recovery is an assault on authority at the most fundamental level, because it destroys the very meaning of the capitalist idiom, denying the Western construction of the individual, and insisting on the inalienability of person and environment.

This is a more fleshed out, studied view of what anarchists were going for when they first took up the call, “land and freedom.” It is no coincidence that anarchists, open to the possibility of learning from other struggles rather than imposing a unifying dogma, adopted this slogan in part from indigenous people fighting in southern Mexico in the days of Zapata and Magon. Marxists, meanwhile, declared such a posture to be reactionary, believing that agriculture had to be industrialized and taking for granted, therefore, the alienation between person and land.

At a panel discussion about repression in the communities, the Mapuche youth organizing the event hung a banner over the speaker’s table that read: Wallmapu liberado, sin cárcel ni estado. “Wallmapu freed, without prison nor state.” They have living memory of a stateless, decentralized society, and with this memory as a lens, all coercive institutions, from prisons to schools, appear as building blocks of their colonization.

Given the importance of these affinities, along with the sincerity and dedication of the Mapuche I have met and the resilience of their struggle, I am inclined to pay attention to the differences. Not because I think we can or should copy the Mapuche struggle, nor out of a romanticized idea that their struggle has no failings. But it is a powerful, inspiring struggle, and the differences between their version of a stateless struggle and our own cannot help but aid us in reflecting on our own strategies.

A couple of the people we got to know in Lof Pañgihue were remarkably upfront with their criticisms, though they made it clear that those criticisms came from a place of respect. They praised Chilean anarchists for their consistent, disinterested solidarity with the Mapuche struggle, and noted that they were piqued when they saw that anarchists were fighting against the State, placing bombs, and going to prison; clearly these were committed enemies of the established order. However, they did not have a clear idea of what the anarchists were fighting for. Those who had spent time in the city had seen anarchist social centers and libraries, but what were the anarchists actually trying to create?

All the major leftist anticapitalist groups in earlier decades had used the Mapuche as footsoldiers and “the Mapuche conflict” as a mere source of discontent. It became clear to many that should the Marxist guerrillas ever win, they would only impose a new Western order on Wallmapu, as had happened to every other indigenous nation when Marxists had taken over. For them, independence specifically meant not being subordinated to a state.

The anarchists had only been around for a short time in Chile, eight years in their estimation. Because it was not clear what the anarchists wanted, they were cautious that they might also be fighting for power. Should they ally with anarchists and win, would the anarchists accept that they did not have any say on what happened in the lands south of the Bío Bío river, or would they also try to impose on the Mapuche territories? Did the anarchists have an answer for the “Mapuche conflict” or would they respect Mapuche autonomy?

They did not understand why solidarity events at the anarchist social centers often turned into parties. What did the parties have to do with the struggles or prisoners they were supporting? Mapuche solidarity events often focus on letting people know why they are struggling, and the rightness of their struggle, or on holding a ceremony that would bring newen to their prisoners.

They also asked why so many anarchists were vegans, not seeing a connection between respecting animals and not eating them. Fortunately, most of the anarchists they had met, in addition to being vegans, held strong criticisms of civilization. I worry that, had their prior experience been with leftist anarchists who believed in the narrative of civilization and progress, they might never have reached out to us. As it was, none of us were vegan, and all of us were critical of civilization, so we got along just fine.

Then there were a couple specific grievances they had, both relating to Chilean anarchists. One was an occasional imposition of rhythms, as when a group of masked anarchists started smashing banks at a Mapuche solidarity demo in Santiago. The Mapuche were not opposed to smashing banks, quite the contrary, but they did object to what seemed like anarchists trying to speed up their struggle.

The other grievance related to a video they had seen on TV of a Santiago anarchist transporting a bomb which blew up prematurely. The surveillance video portrayed the anarchist catching on fire, and his comrade running away and leaving him there. The Mapuche would never abandon a comrade like that, they said. They attributed it to inexperience on the anarchists’ part. One question they asked us frequently was how long we had been involved in the struggle and what had made us become anarchists.

The other grievance related to a video they had seen on TV of a Santiago anarchist transporting a bomb which blew up prematurely. The surveillance video portrayed the anarchist catching on fire, and his comrade running away and leaving him there. The Mapuche would never abandon a comrade like that, they said. They attributed it to inexperience on the anarchists’ part. One question they asked us frequently was how long we had been involved in the struggle and what had made us become anarchists.

A Mapuche friend who was close enough to not have to worry about politeness chided us anarchists for not having newen. This will be an especially difficult difference to explain, especially since the closest analog to newen among North American anarchists is “woo” or “magic,” and the concepts seem completely different in practice. Suffice it to say that a comparison would be misleading. In my experience the Mapuche are very matter-of-fact about newen. Beyond simply rejecting a mechanical, scientific view of the world, as do many anarchists, the Mapuche live out a different worldview that is firmly anchored in the totality of their economic, spiritual, and physiological life, and therefore they do not relate to newen as a performance in an alienated spiritual sphere.

I will point to a few other differences pertaining directly to the Mapuche vision of struggle that I think can be instructive for anarchists.

The Mapuche in struggle are far from pacifist. On the contrary, sabotage, direct action, self-defense, and the attack are assumed as an integral part of their struggle, and the topic of burning things down is a constant source of mirth and laughter, exactly as it is with anarchists (which is surprising, given that humor is often the first thing not to translate). The similarity ends there. Not every Mapuche is expected to be a weichafe, or warrior, and the weichafe are not the central participants in the struggle. The weichafe are not more important than the machis, the werken, or the weupife. On the contrary, the weichafe are at the service of the community, and their activity is in a certain sense meant to complement and be guided by the activity of the rest of the community.

The Mapuche have a lot of prisoners, and they do an excellent job of supporting those prisoners. But they do not fall into presismo, or a detached focus on their prisoners, an activity that certain anarchist circles present as the most radical. On the contrary, their focus remains on the struggle that resulted in people falling prisoner in the first place. The assertion that a powerful struggle supports its prisoners can be taken in two directions, after all. Supporting prisoners so that the struggle will be stronger, or strengthening the struggle so that the prisoners will be supported.

The Mapuche have a lot of prisoners, and they do an excellent job of supporting those prisoners. But they do not fall into presismo, or a detached focus on their prisoners, an activity that certain anarchist circles present as the most radical. On the contrary, their focus remains on the struggle that resulted in people falling prisoner in the first place. The assertion that a powerful struggle supports its prisoners can be taken in two directions, after all. Supporting prisoners so that the struggle will be stronger, or strengthening the struggle so that the prisoners will be supported.

Connected to the Mapuche success in supporting their prisoners and resisting heavy state repression, at least in my mind, is the long-term view that the Mapuche typically take. One can often hear the phrase, “We have been struggling for over 500 years, and we may have to struggle 500 more.”

This is interesting because the historical referent that frames this view—colonization—should be equally important to people of European descent and to anarchist theory itself. The State swelled exponentially with the early beginning of capitalism. What the Spanish state tried—and failed—to do to the Mapuche had already been done across Europe. The alienated worldview that anarchism has struggled with for its entire history, sometimes discarding it, sometimes reifying it, comes down to the separation of land and freedom which is the essence of colonization and all the political movements against colonization that have won freedom without land and land without freedom.

The same long view that could allow us to make historical sense of this alienation can also give us the patience to weather repression. As urgent as a particular case of repression may feel, we will not answer the broader questions of repression in our lifetimes, but we also do not face them alone: we have gone through all of this before.

A common criticism that anarchists might have of the Mapuche struggle has to do with gender. But this criticism should be put into perspective. As a friend in the project aptly put it, “Our opinion about gender in Mapuche society doesn’t matter.” It would also be wrong to assume that our opinion is entirely external. In fact, it was a criticism shared by several Mapuche comrades, although they tended to frame it in a different way.

We were able to talk frankly about gender with several of the lamuen and peñi we were closer with. Many of them said that the machismo of Chilean society had rubbed off on the Mapuche, which was traditionally not a patriarchal society. However, accepting that assertion requires allowing for a distinction between patriarchy and gender binary. In Western history, patriarchy and gender binary are largely inseparable. But are we willing to assert this as a global truth? Mapuche society is built around a traditional division of gender, but this division constitutes two autonomous spheres of activity, rather than a hierarchy. In practice, women are full participants in the Mapuche struggle. Some spaces of this struggle are mixed, others are separate, but none are made invisible or subordinate. The question that we as outsiders are unable to know is, what happens to those Mapuche who do not accept their assigned role?

Gender roles are gradually changing within the Mapuche struggle but, for better or for worse, the rhythm, form, and ends of that change are not necessarily recognizable to a feminist mode of struggle.

What Made This Project Possible

I hope comrades will take it as a matter of high standards and not self-congratulation if I describe this project as a great success that goes far beyond the complacency and repetition of most anarchist projects. It was not a success because those who made it happen are particularly successful anarchists; on the contrary, we probably aren’t. It was a success because we were able to identify our weaknesses and find comrades with the skills necessary to shore up those gaps.

In order to encourage better anarchist projects, I wanted to identify the prerequisites for making it happen. Although the project was a joint affair with Mapuche comrades, I can only talk about our side of things.

The most vital element were relationships of friendship and solidarity. These could only form face to face, sharing moments of struggle and of daily life. This is an indictment of the superficial solidarity of communiques, or the abstract solidarity of NGOs, both of which commit to the idea of a distant struggle, and are therefore incapable of enabling a solidarity intense enough to challenge our practice. The relationships that enabled our project could only form in a healthy way if people on both ends were committed to their own autonomous struggles, but willing to find points of contact and affinity between those struggles. This is an indictment of ally politics. Someone who is only an ally can never offer anything more than charity. Those who believe they are so privileged that they do not have their own reasons for fighting have nothing to offer anyone else. But we also had to recognize the fundamental difference of the Mapuche struggle, staying true to our beliefs but not trying to impose them.

Personal relationships created the possibility for a deeper solidarity, but technical skills were necessary for transforming that solidarity into an intensification of the struggle. Liberal arts education is a wasteland that imprisons North American anarchists. Without technical skills, we condemn ourselves to an anarchism of abstraction, incapable of rising above dependence on the structures of dominant society.

No one on this trip had the skills necessary to complete the project. But together, and with a lot of help from the peñi we worked with, we were able to pull it off by the skin of our teeth. This gave us the confidence and the experience to do something like this again. The rural Mapuche had the experience of building their own houses, and a couple of us had learned welding or at least a very basic familiarity with hand tools through squatting or an interest in tinkering. This might have barely been enough to construct one of the simpler water systems. But the more complex of the systems we were working on would have been entirely out of our reach had one of the comrades not had an attribute rare among anarchists these days: years of experience working in a factory. These extensive technical skills, however, would have been inadequate without the aid of those practiced at adapting to chaotic situations and scarce materials. Working in a factory, in the end, is nothing like working in the field. So the technical genius of the anarchist factory worker who participated on the project was completed by the practical genius of the Mapuche comrades who were used to making everything out of nothing. And finally, until all anarchists are polyglots, translation will be a necessary skill for international projects like these. However, translation alone can only enable projects centered on propaganda.

The skills we are talking about, in other words, go far beyond hobbies. We are talking about years of experience to acquire abilities that most of us lack, in order to overcome very immediate limitations to our struggle.

The skills we are talking about, in other words, go far beyond hobbies. We are talking about years of experience to acquire abilities that most of us lack, in order to overcome very immediate limitations to our struggle.

Finally, this project relied on a strategic projectuality. This means identifying our weaknesses and crafting projects that might overcome them, projecting ourselves into the breaches where our struggle might be overwhelmed in the near future. This is the opposite of doing for the sake of doing, or carrying out a predetermined and repetitive set of activities, which is how many anarchists spend their time.

The Mapuche had identified their lack of land, and they began to recover that land. Only within the situation they had created were we able to work on such a project together and learn things that may be useful in addressing weaknesses we face on our own turf.

The original solidarity trip three years ago was an attempt to overcome an identified weakness in the international relationships of US anarchists. That trip made it possible for Mapuche comrades to suggest the present project to us, allowing our solidarity to advance to a new level. This is an indictment of those anarchists who either travel for mere personal pleasure, or those who use the contacts they cultivate as a form of social capital to hoard.

When the Line between Self-Sufficiency and Sabotage Becomes Fine

Why is it that in a context of total alienation, projects that focus on self-sufficiency or going back to the land almost invariably entail a cessation of hostilities with the State and a recuperation by Capital? The answer is probably equally related to the implications of buying the land or space for one’s autonomy, and a spiritual acceptance of the a priori alienation between person and environment.

An attempted development on Mapuche lands burnt down.

The Mapuche struggle involves the forceful recovery of land they uncompromisingly claim as theirs, and a way of being—by this I mean a seamlessly interlocked spirituality, economy, and social organization—that declares war on the alienation between person and environment. In this way of being, there is no dividing line between gardening, home-building, natural medicine, setting fire to logging trucks, clashing with cops, sabotaging construction equipment, or blocking highways.

Self-sufficiency signifies a contraction of one’s relationships and an avoidance of the lines of social conflict. One who is self-sufficient need not form relationships with others. But the claiming of space and the inalienability of one’s relationship to that space asserts an expansive web of relationships that we must defend in order to truly be alive.

In my free time in Wallmapu, I learned to harvest and thresh quinoa, to kill and gut a chicken, and to gather certain wild plants. In that particular context, these were not hobbies that might eventually be put to use in a strategy of avoidance. Capitalism has been very deliberate in deskilling us, which is a way of robbing us of the possibility of intimately relating with the world around us. “Relating with the world around us” is not a leisure activity, as the bourgeois imagination would have us believe. It does not mean (only) walking barefoot and spending time with nature, or playing games and having picnics in the park. It also means feeding ourselves, healing ourselves, housing ourselves, and a hundred other activities. Doing things directly always requires relating with other living beings rather than relating with commodities. Feeding ourselves, within an offensive practice that seizes space from the State, is not at all a form of avoidance, but an intensification of our freedom and our war on the State.

The people in Lof Pañgihue were very clear: being able to produce their own electricity would be a powerful form of sabotage against the State. Theirs was not a case of middle class people putting solar panels on their houses, selling the surplus back to the power company, and living with a cleaner conscience. It is a war to recover their territory, to kick out the State, the capitalists, and the Western way of life. If they end their dependence on the State’s infrastructure, not only have they intensified their practice of independence, they have also made that state infrastructure vulnerable to attack.

A logging truck in the Mapuche territories

It is often said that there is no outside to capitalism. This is certainly true as far as capitalist projectuality is concerned, but the statement does not truly define our counter-activity unless we accept alienation as a physical feature of reality. Where land is being retaken as a part of ourselves, building the tools and developing the lost skills that allow us to relate directly to that land and to live as a part of it constitute a practice of independence from and against capitalism.

Our freedom is not merely a blank slate or the lack of imposition by the State. Freedom must be articulated ever more intensively, through the tools, skills, worldview, medicine, historical memory, food culture, and material anchors that constitute the becoming or the embodiment of that freedom.

Glossary

Bío Bío—a river that runs west from the Andes and empties into the Pacific at the modern day site of Concepción. For hundreds of years, this was the treaty-guaranteed northern boundary of the Mapuche territories.

che—person or people

gringo—European or North American

lamuen—sister or compañera

latifundistas—major landowners, a holdover from the colonial system of production

lof—a Mapuche village community

longko—the closest translation is chief, although not a coercive figure and only one of several vocational authorities at the community level

machi—medicine man, a spiritual leader and healer (can be man or woman)

mapu—land, earth, territory, or space

newen—force or strength, of the kind that flows from nature

peñi—brother or compañero

presismo—prisonerism, a dead-end practice of obsessively or ritualistically supporting prisoners, often in a fetishizing way

rewe—a voluntary aggrupation of lof in a contiguous local territory

Wallmapu—the Mapuche territories, or “all the lands”

weichafe—warrior

werken—literally a messenger, a community authority responsible for working on behalf of the community and maintaining connections with other communities

weupife—a person in a community responsible for maintaining and transmitting the collective historical memory

winka—literally “New Inca,” meaning white person or non-indigenous person